Ritika Pandey, a 3rd year Student from Galgotias University has written this Article on”Doctrine Governing Centre & State Legislative Relations”.

INTRODUCTION

All legislative, executive and financial powers are divided between the centre and the states according to the Indian constitution. The relationship between the Union and States is governed under Articles 245[1] to 293 [2]of Indian Constitution. The distribution of powers is an essential feature of federalism. A federal Constitution establishes a dual polity, with the Union in the Centre and the States at the periphery. Each is equipped with sovereign powers to be exercised in the field assigned to them respectively by the Constitution.

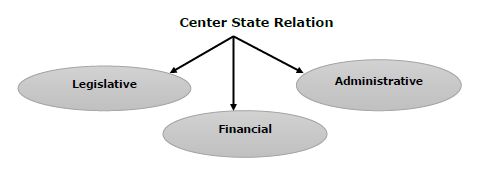

There are three types of relationships involved in centre -states relations:

- Legislative Relations

- Administrative Relations

- Financial Relations

LEGISLATIVE RELATIONS

Article 245 to 255 [3]of the constitution deals with the legislative relation between the centre and states. Indian constitution also divides the legislative power between the centre and states with respect to both territories and the subjects of legislation.

There are four aspects of the legislative relationships between the union and the states:

- Territorial extent of central and state legislation

- Distribution of legislative subjects

- Parliamentary legislation in the state field

- Centre’s control over state legislation

Territorial Extent of Central and State Legislation

Parliament has the authority to enact laws that apply to all or a portion of India’s territory. The state legislature can enact laws for the entire state or just a portion of it. Unless there is a strong link between the state and the object, state laws are not applicable outside state. Parliament is the sole institution having the authority to enact “extraterritorial” laws.

Situations in which the following don’t apply to legislative laws:

For the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Ladakh, and Lakshadweep, the President has the authority to issue regulations that have the same force and effect as laws passed by parliament.

The governor has the authority to order a parliamentary act. That either applies with certain modifications and restrictions or does not apply to certain state territories.

Distribution of Legislative Subjects

The three divisions established by the constitution are the Union List, State List, and Concurrent List. When it comes to the Union list, Parliament alone has the last say. The state legislature usually has the authority to enact laws relevant to the items on the state list. On the topics listed in the concurrent list, both the state and federal governments have the authority to pass legislation. Parliament has the authority to enact legislation having a recurrent topic. State lists are given lower priority than concurrent lists, and union lists are given higher priority than concurrent lists.

The Parliament has the authority to enact laws pertaining to ancillary matters.

Parliamentary Legislation in the State Field

The Constitution permits Parliament to enact laws on any topic included in the state list under the following four exceptional circumstances:

- When Rajya Sabha approves a resolution with the support of two-thirds of the members present and voting. This will empower Parliament to enact legislation on state-list issues in the best interest of the nation. Such a resolution lasts for a full year. This resolution can be renewed multiple times but not for more than a year at a time. The laws passed in accordance with the resolution cease to be in force six months after it was adopted. In the event of a disagreement between state and union legislation, the latter prevails. A state may, however, pass legislation on the same issue.

- During a national emergency, Parliament can pass laws on any matter related to the state list. The legislation passed under this is only valid for six months before they expire. State laws may apply, but union law takes precedence in case of conflict on the matter.

- If a state passes a resolution requesting Parliament to act on a list of issues, Parliament is authorized to act. The state forfeits all rights there once this resolution is approved. To implement International Agreements, the parliament can make laws on any matter in the state list for implementing International Treaties, agreements and conventions.

- The imposition of the President’s Rule in a state empowers Parliament to make laws regarding any matter in the State List.

Centre’s Control Over State Legislation

According to the Constitution, the federal government is authorised to exercise the following influence over state legislative affairs:

- Specific laws established by the state legislature may be set aside by the governor for presidential consideration. They are entirely under the president’s power.

- Bills on specified subjects listed in the state list can only be filed in the state legislature with the President’s prior consent. For instance, interstate trade and commerce.

- The President may ask a state to lay aside money bills and other financial bills for his consideration in the case of a financial emergency.

Doctrine Governing Centre & State Legislative Relations

1) The Doctrine of harmonious construction

This rule is well settled and says that when there are in an enactment to provisions which cannot be reconciled with each other, they should be so interpreted that, if possible, the effect should be given to both. This rule was first expounded by Chief Justice Gwyer in Re Central Provisions Berar Act, 1938 and since then has been consistently followed by the Courts.

This theory was developed to promote harmony among the many lists mentioned in Schedule 7 of the Indian Constitution. When an entry on one list crosses over onto another, the doctrine is applicable. It is the responsibility of the courts to avoid conflicts between two laws. Moreover, whenever possible, interpret sections that seem to be at odds with one another in a way that brings them into harmony. Given that both clauses were created by the legislature and given equal legal standing. So, it can be assumed that if the legislature intended to grant something, it would not have planned to take it away with the other.

A provision of a single act cannot render another provision of the same act ineffective. The legislature cannot, therefore, be expected to contradict itself under any circumstances. The principle of harmonic construction also applies to cognate Acts like the Code of Civil Procedure and Court Fees Act. However, it would be unreasonable and illegal for the Court to arbitrarily limit the scope of those words in order to create harmony between the presumptive object and the Act’s design if the words of the statute are not reasonably capable of the interpretation proposed This is any important Doctrine Governing Centre & State Legislative Relations

CIT Vs. Hindustan Bulk Carriers

In the landmark case of CIT Vs. Hindustan Bulk Carriers [4]– In this case, the Supreme Court laid down five principles of rule of harmonious construction: –

- The courts must avoid a head-on clash of seemingly contradicting provisions and they must construe the contradictory provisions so as to harmonize them.

- The provision of one section cannot be used to defeat the provision contained in another unless the court, despite all its effort is unable to find a way to reconcile their differences.

- When it is impossible to completely reconcile the differences in contradictory provisions, the courts must interpret them in such a way so that effect is given to both provisions as much as possible.

- Courts must also keep in mind that an interpretation that reduces one provision to a useless number or dead is not harmonious construction.

- To harmonize is not to destroy any statutory provision or to render it fruitless.

2) The Doctrine of Pith and Substance

The Canadian Constitution is where the notion of “pith and substance” originated. From a legal perspective, the Canadian case of Cushing v. Dupuy (1880) [5]is where the idea of pith and substance first emerged. In that case, it was held that the true nature of the bill shall be taken into consideration to decide any dispute relating to the power of making laws. Our Constitution’s Article 246, which was modelled after the Canadian Constitution, categorises the legislative authority of the federal and state legislatures into three lists. When there is a disagreement, the court must consider the law’s provisions and determine which list it falls under.

As per the Black Law Dictionary, the term ‘pith and substance’ means the ‘true nature or character’ of a law. According to this idea, state legislatures and the Parliament are each supreme in their own spheres and should not infringe on one another’s jurisdictions. In order to determine the genuine substance of the law in the event of any controversy over the legal area, we must consider the true nature or features of the law. This will make it easier to assess the legitimacy of the legislature and the true character of the law.

While examining the content of the law, there will be two outcomes, which are as follows

- If the substance of the law corresponds to the subject on which the legislature has the power to make laws, the enactment of the law will be perfectly valid;

- If the substance of the law doesn’t correspond to the subject or it is outside the jurisdiction, it will result in partial or accidental encroachment in the domain of another organ. In that situation, the enacted will lose its constitutional validity.

3) The Doctrine of Colourable Legislation

The Doctrine of colourable legislation can be understood by the example that ‘what cannot be done directly cannot also be done indirectly’ based on the Latin maxim ‘Quando a liquid prohibetur ex directo, prohibetur et per obliquum’. When the court is faced with a case where legislative competence is at stake, the doctrine of colourable legislation enters. In order to determine whether or not that particular legislature has the authority to legislate on the matter, the court will look at whether the challenged statute and its enactment come within its jurisdiction. In that case, the statute would be deemed invalid. It is interesting to note that occasionally the contested legislation appears to fall under its purview, but its actual outcome or intent lies outside of its purview.

The Doctrine of Colourable Legislation records the division of authority among legislative branches. The doctrine’s core idea is that even if a law’s subject matter is outside of its purview, it nevertheless stands void if it was passed in an indirect manner. This Doctrine is essential in India for Governing Centre & State Legislative Relations

As a result, if a legislature is unable to pass legislation on a subject that cannot be dealt with directly, then the same cannot be done indirectly using a constitutionally authorised power.

4) The Doctrine of occupied field

The doctrine of the occupied field indicates a field(s) that is or has been occupied. In India, the Parliament and the State Legislatures legislate on different subjects, which are mentioned in the Union List and the State List, respectively. The Concurrent List allows both Parliament and State Legislatures to make laws together. Some subjects in the State List correspond to entries in the Union List or the Concurrent List. These subjects are under the legislative power of the Union.

The doctrine of occupied fields does not actively mitigate centre-state conflict over legislation. But it simply mentions that certain subjects in the State List are within the purview of the Parliament. An entry attached to the Union List means exclusive jurisdiction for the Parliament. In addition, where an entry is attached to a corresponding entry in the Concurrent List, even though the state government can legislate on matters of the Concurrent List, the law made by the Parliament will be given supremacy, if exclusive jurisdiction does not already rest with the Parliament.

The doctrine of occupied field is found in Entry 52, List I, Entry 24, List II, which when read together, state that the Parliament can make laws to exercise control of certain industries in the public interest, which would render those industries out of the legislative power of the State Legislatures. Further, Entry 7, List I, provides that the Parliament has the competence to legislate over industries necessary in relation to the defence or prosecution of the war. This doctrine governing Centre & State Legislative Relations permits Parliament to legislate on mines, minerals, higher education, and port regulation.

5) Doctrine of Repugnancy

Repugnancy indicates that there exists a contradiction when two laws which are applied to the same facts produce different results. For example, a subject in the Concurrent List is legislated upon by the State Government as well as the Parliament, but the situation becomes incompatible when both sets of laws are applied to the subject. Repugnancy arises when the application of one law violates another law or set of laws.

Article 254(1)[6] states that if a law enacted by the State Legislature is repugnant to the central law which the Parliament is competent to enact, or to a law related to the subject in the Concurrent List, then the law made by the Parliament shall prevail over that of the State Legislature. This can happen in two ways: where the centre has not enacted the law yet, and the state has legislated on the matter, and where the central law already exists, and the state comes out with its own law. State laws conflicting with Parliament laws are null and void.

M. Karunanidhi v. Union of India

A landmark case in this regard was that of M. Karunanidhi v. Union of India[7], In which a constitutional bench of the Supreme Court considered the question of repugnancy. The Court laid down certain points which needed to be kept in mind before the application of the doctrine of repugnance.:

- That there is a direct inconsistency between the law made by the centre and the law made by the state.

- That the inconsistency is such that it cannot be reconciled.

- That the inconsistency is of such nature that it brings into collision the two laws.

- That the inconsistency is such that a situation cannot be reached without disobeying one or the other law.

- A law cannot be repealed merely because of an indirect conflict; there must be prima facie repugnancy. If two laws don’t conflict, the doctrine doesn’t need to be applied.

Deep Chand v. State of Uttar Pradesh

In Deep Chand v. State of Uttar Pradesh[8], the Court held the following three points as determinants of repugnancy:

- There is a direct conflict between the two provisions

- The two conflicting provisions of the Parliament and the State Legislature(s) occupy the same field

- The enactment of the Parliament is exhaustive and was formulated to replace the enactment of the State Legislature(s)

6) Doctrine of Severability

The Supreme Court developed the doctrine of severability, also known as the doctrine of separability, to address the validity of laws that have been found to be unconstitutional. Thus, the question of whether the entire Act should be declared unconstitutional when only a portion is void arises.

Article 13 [9]of the Indian Constitution provides for judicial review of any law or portion of a law that is found to be unconstitutional or to violate fundamental rights. In accordance with the Article, the doctrine of severability states that a law is only declared void to the extent that it is inconsistent with or in violation of the Fundamental Rights of the Indian Constitution.

According to the doctrine of severability, only the offending component of a statute or act that is in conflict with or objectionable to the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution would be deemed invalid, not the entire statute or act.

The main tenet of this approach is not to repeal the entire statute but simply the problematic provisions that violate the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. So, in any Act, if a good provision and a bad provision are combined and or, if the good provision is independent of the bad provision, the bad provision can be separated and declared unlawful, and the good provision will still be regarded as being in effect. In conclusion, all Doctrine including Doctrine of severability is important and essential Governing Centre & State Legislative Relations

[1] India Const. art. 245

[2] India Const. art. 293

[3] India Const. art. 255

[4] CIT Vs. Hindustan Bulk Carriers, AIR 2002 SC 3491

[5] Cushing v. Dupuy (1880)

[6] India Const. art. 254(1)

[7] of M. Karunanidhi v. Union of India, 1979 AIR 898

[8] Deep Chand v. State of Uttar Pradesh, 1959 AIR 648

[9] India Const. art. 13

![]()

Leave feedback about this